Tate Museum Mammoth Skull

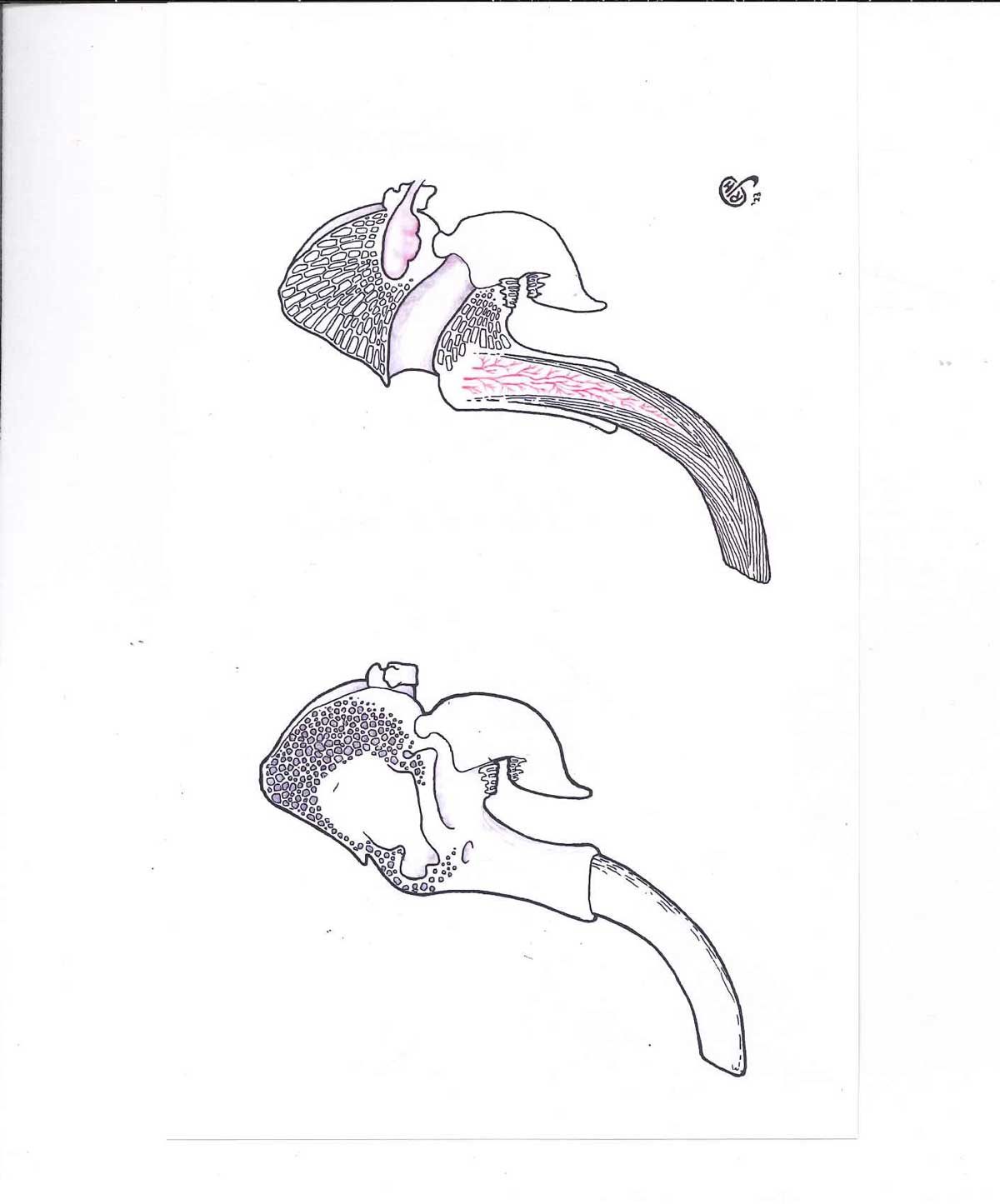

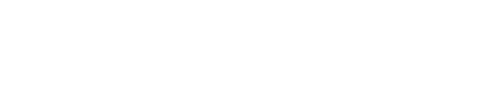

From the outside a mammoth skull looks heavy and solid, but if you break it open, the inside looks a bit like an egg carton – the interior is divided up into a complex of air-filled cells separated by thin, intersecting sheets of bone. If you’re a mouse looking for a home, the skull of a dead mammoth is a ready-made condominium with dozens of rooms available. All you have to do is get inside.

When Dee’s skull was finally discovered there turned out to be some small holes chewed into it – it was hypothesized that these had been made by rodents. Tate volunteer Dwaine Wagoner collected soil from around Dee’s skeleton and screen-washed it, then meticulously examined the coarser material under a dissecting scope, looking for bones. Sure enough, he found the tiny skeleton of a harvest mouse (Reithrodontomys). Tate staff named the mouse ‘Harmony.’ Harmony probably came across Dee’s bones several months after the mammoth died. The ten-ton mammoth and the 15-gram mouse were the only skeletons found at the site.

Mammoth tusks were made out of multiple layers of ivory, one nested inside of the other like a stack of snow-cones. The proximal third of the tusk was hollow, with a conical pulp cavity filled with nerves, blood vessels and other soft tissues. The anterior half of Dee’s left tusk broke off at some point during his life, probably lost in a fight with another mammoth. Fortunately for Dee, the tusk broke at a point distal to the pulp cavity where it was solid ivory all the way through, so the damage wasn’t too painful and there was little danger of infection.

Left: Dee’s skull, outer layer of bone removed to show the air-cell complex inside.

Right: Dee’s skull, cut in half to show the air cells in cross section. Also shown are the blood vessels in the pulp cavity (in red), the cavity for the brain (pink) and the air passage running from the throat to the nasal opening for the trunk.